On this page…

Areas of Action: Your Food

A sustainable diet helps to mitigate climate change through the protection of natural ecosystems, reducing waste and pollution, improving our health, reducing food insecurity and supporting sustainable agriculture here and around the globe.

What needs to change?

A carbon intensive, wasteful, polluting diet and unsustainable agricultural practices.

Climate friendly, more circular/less wasteful, more healthy diet and sustainable/regenerative agricultural practices.

Why is this so important?

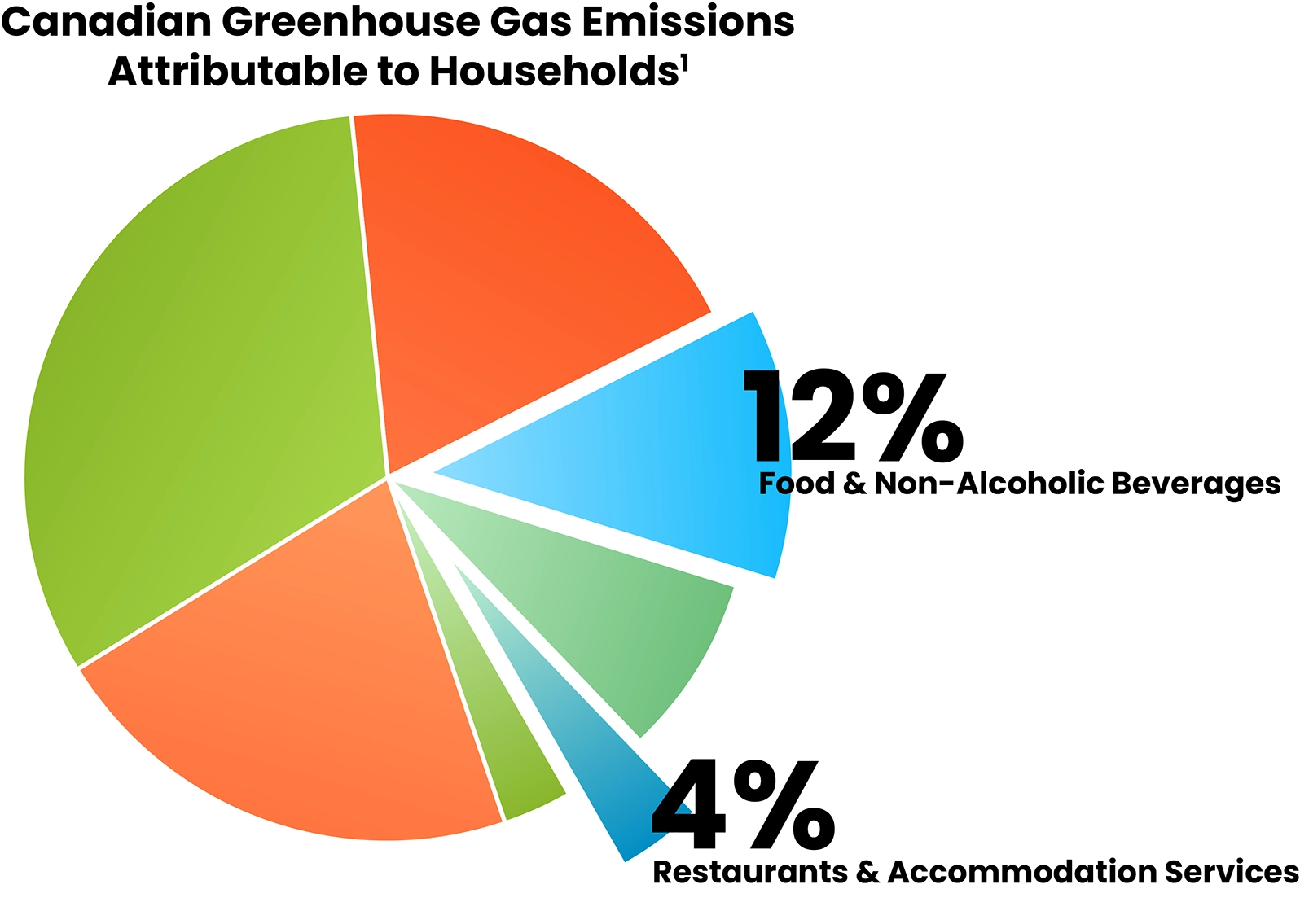

Food and non-alcoholic beverages account for 12% of household emissions. A portion of the restaurant and accommodation category is also impacted by our dietary choices as well.

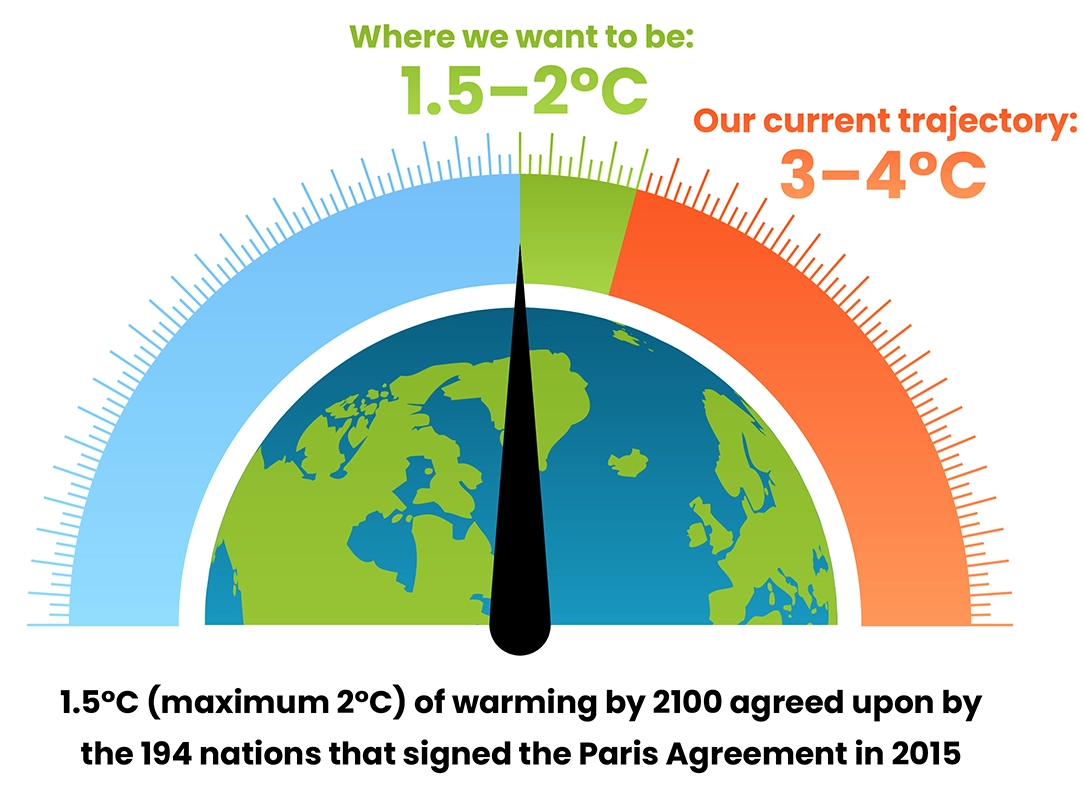

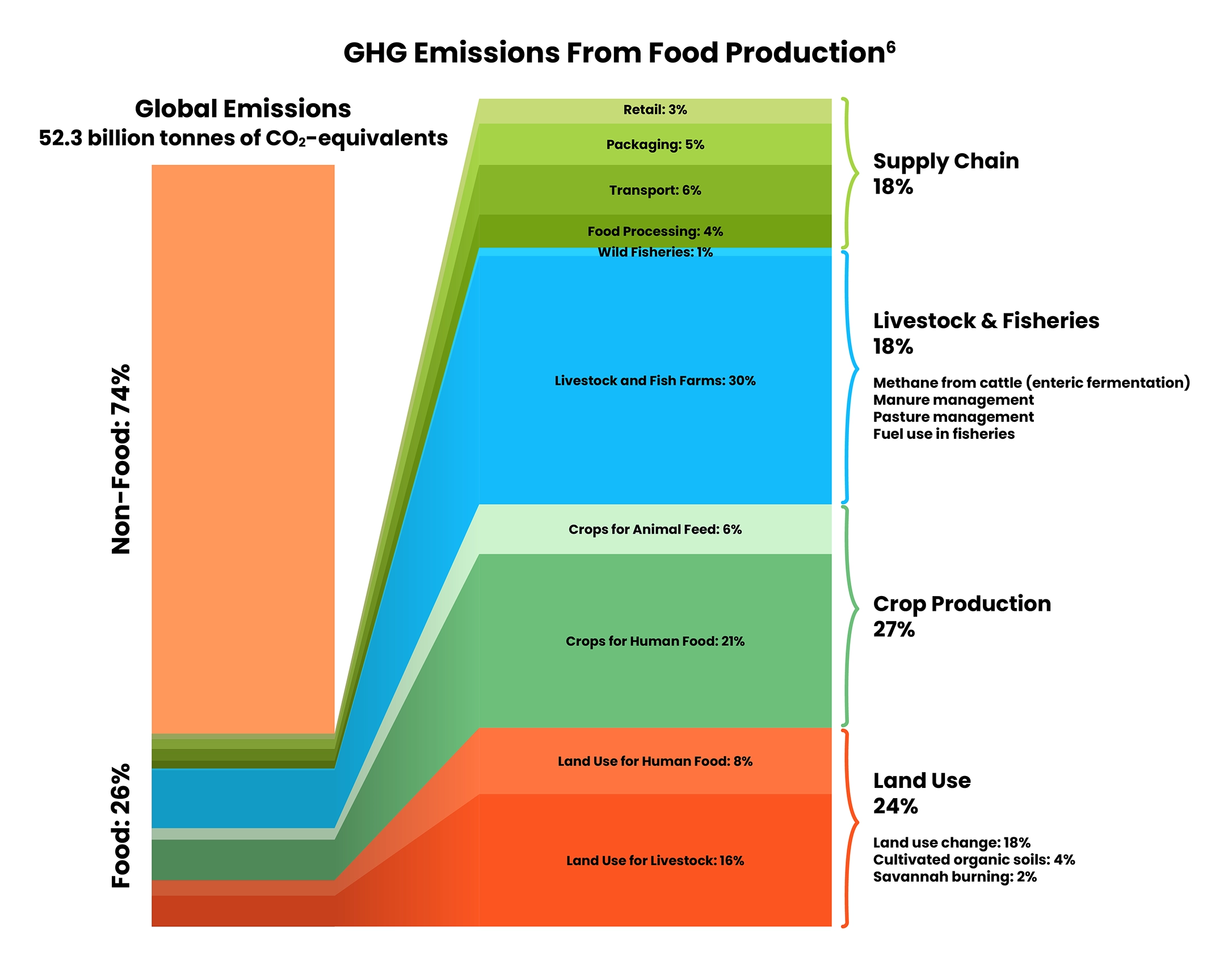

Globally, food systems account for about 25–30% of our greenhouse gas emissions2. This is so big that even if we stopped using fossil fuels tomorrow, our food system would still push us past the 1.5°C threshold3. We have to change how we eat.

Some of the major trends towards decarbonization are 1) to switch to a more climate friendly diet — at least temporarily in some cases until sustainable alternatives are available 2) support for sustainable and regenerative agricultural practices and 3) reduction of food and food-related waste.

Most of our individual action in this area will be through our food and brand choices.

Why so urgent?

There is a rapidly narrowing window of time to implement existing commitments and raise ambition4. See Why So Urgent?

As per the Paris Agreement and subsequent IPCC modelling and research updates, we need to reduce our emissions by 43% below 2019 levels by 2030 in order to have a good chance of hitting Net Zero emissions by 2050 and avoiding the worst impacts of climate change.

Low Carbon Diets

Although vegan diets are the most sustainable and climate friendly5, you don’t have to become a vegan to have a significant positive climate impact.

What would be most helpful is:

1) Cutting out — or significantly scaling back on — the most carbon-intensive parts of your diet at least until there are climate friendly versions of them and/or

2) Purchasing low carbon versions of traditionally high carbon foods where possible.

In addition, there are many opportunities to also support 1) societal shifts to Regenerative Agriculture and a reduction of food waste and 2) other local and global issues and SDGs as desired such as plastic pollution, the water crisis, food insecurity, gender equality, health and wellbeing and more.

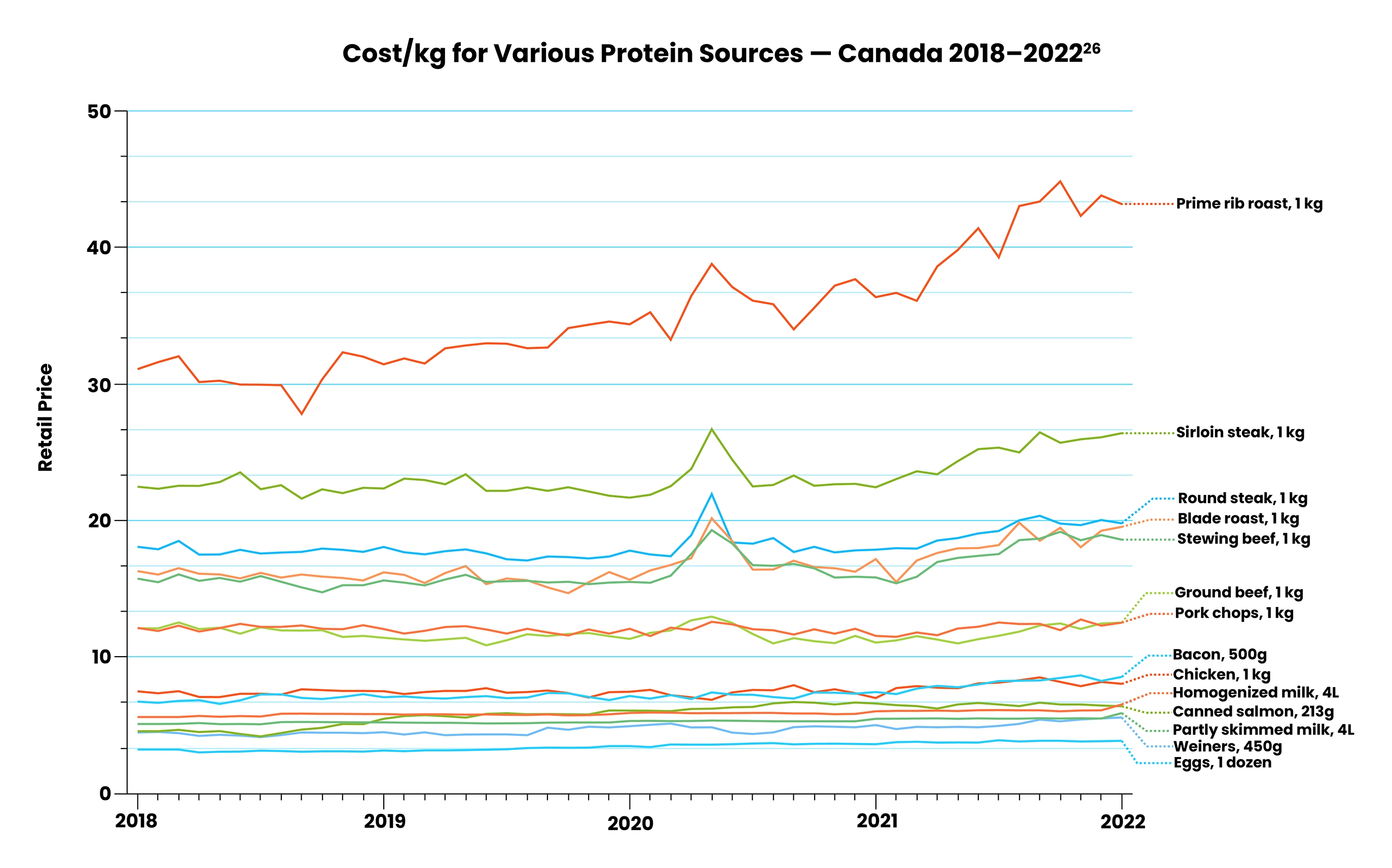

A climate friendly diet can also save you money.

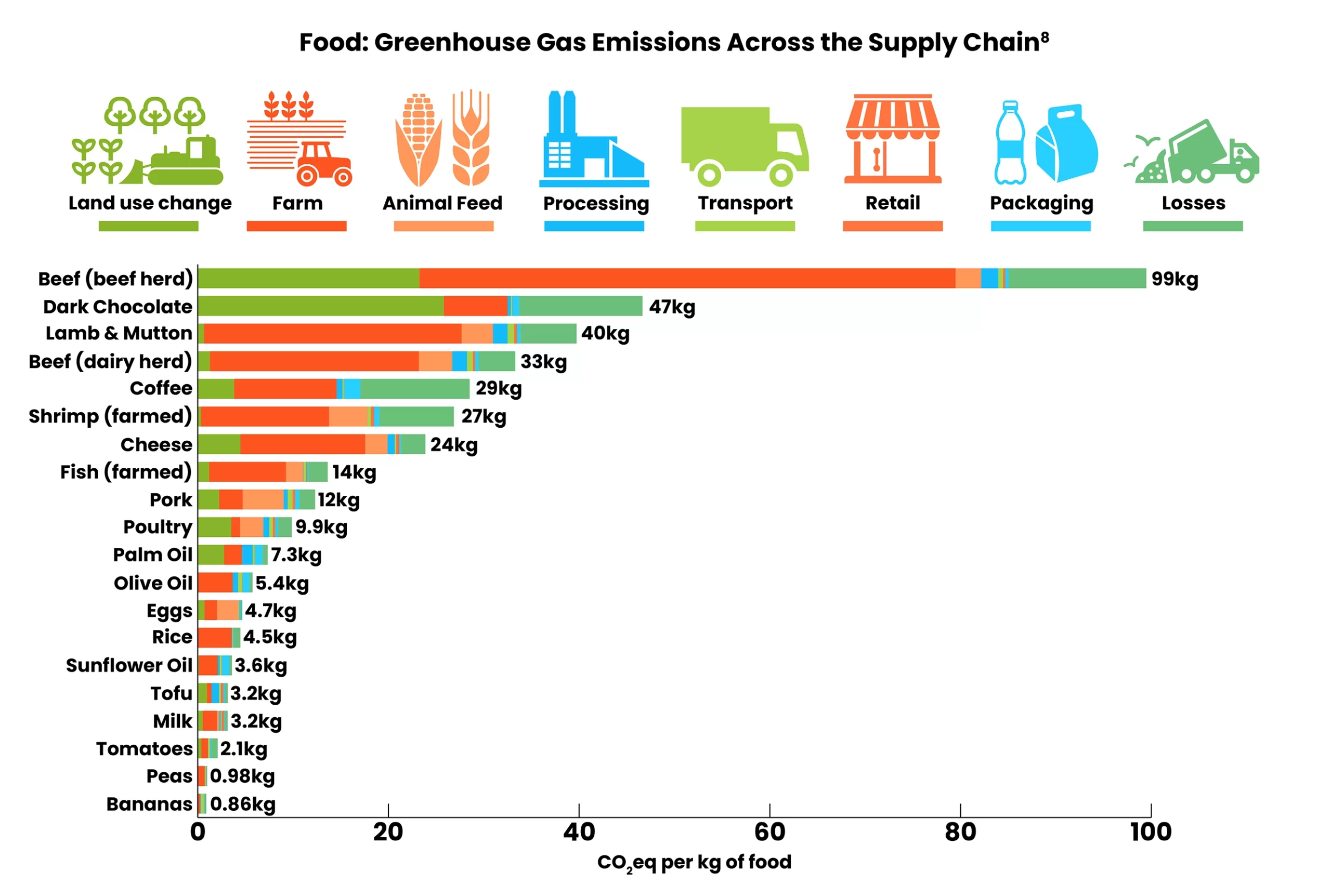

The main contributors are not just the fossil energy needed during production, processing transport, packaging and retail, but also methane from food waste, the methane from manure and enteric digestion (primarily from beef and lamb), nitrous oxide in fertilizers used for both livestock feed and crops we consume directly and land use and land use change activities (eg deforestation for cattle ranching).

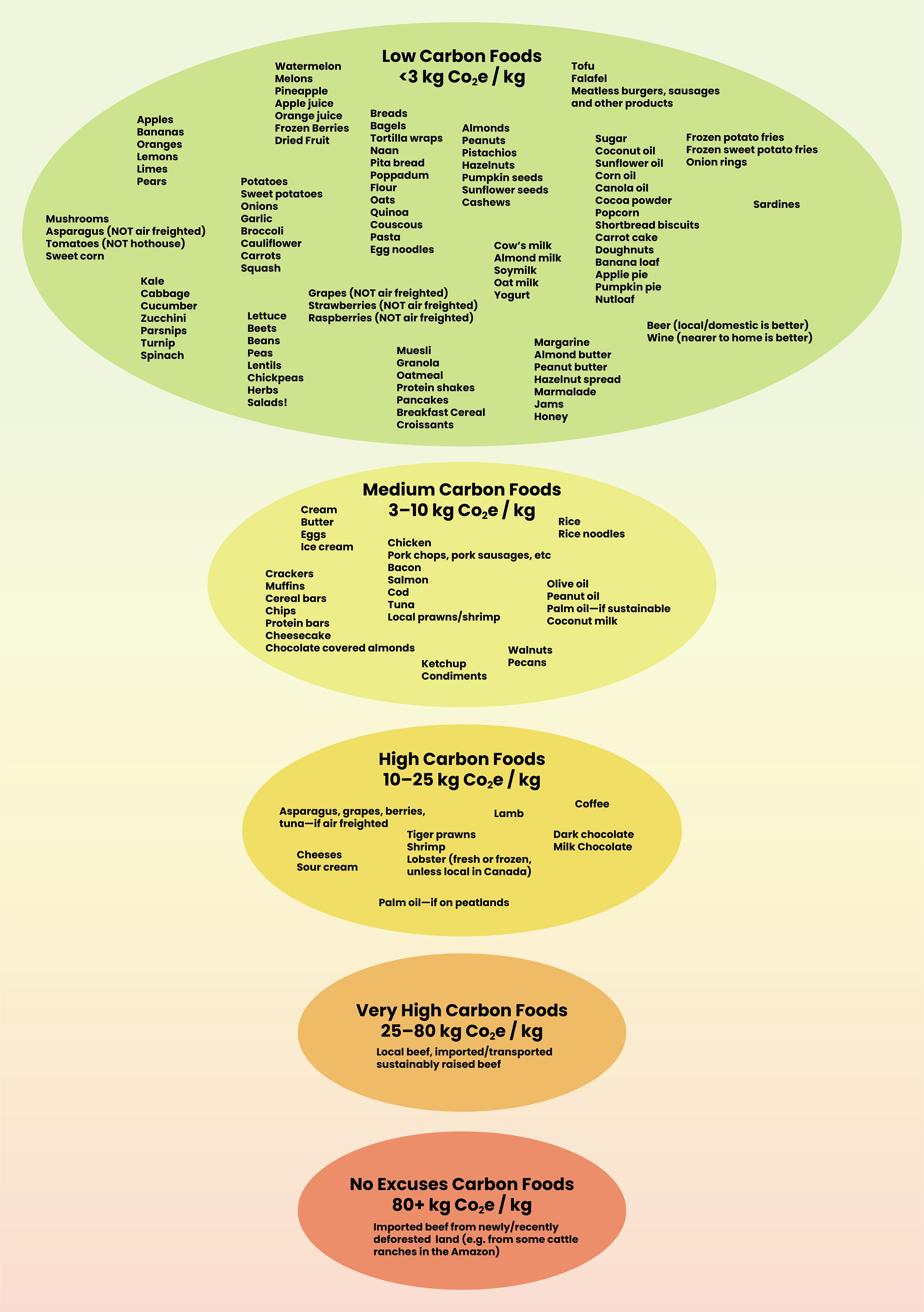

Which foods are carbon friendly or carbon intensive? There are a lot of foods that are climate friendly and much fewer that need to be eaten in moderation or temporarily cut out of your diet.

Note that some carbon intensive foods are typically eaten in small quantities — like parmesan and sour cream, so are not as concerning as ones that are eaten in larger quantities.

Check out these sites as well if you want to do some research on particular foods:

CarbonCloud (note the stage in the lifecycle — ie. Each entry might only be for a part of the lifecycle and not the whole footprint)

CO2 Everything: Food (note this one is based on a typical serving of food, not a kilogram of food)

Free food Carbon Footprint calculator (note this one is based on a typical serving of food, not a kilogram of food)

Variation in carbon footprints for a given type of food

The Carbon Footprint of a particular food item will vary depending on a lot of factors (geography, seasonality, farming practices, mode of transportation, deforestation considerations, distance shipped) and the important factors will vary based on the food7.

Overall, there will be consistency across sources from a low/medium/high perspective and what you eat will be a more important factor to focus on than where it comes from.

Things to think about

For all foods, and especially for the carbon intensive ones, there are a few rules of thumb you can use to reduce your Carbon Footprint:

Replace carbon intensive foods with delicious alternatives where possible, at least part of the time

If you can cut out or cut back on meat and dairy, this will have the biggest impact on your dietary emissions. However, if you eat meat, tend towards chicken, pork, fish, and squirrels (just kidding) over beef and lamb. The single biggest positive change you can make is to reduce or temporarily suspend your consumption of beef and lamb.

With respect to beef, it is simply not enough to buy local — since transport of beef has a relatively small impact — or even switch to grass fed beef — which is not a sustainable solution at scale.

Why is beef so bad for the climate?

There are multiple sources of greenhouse gases from beef production9:

• The methane due to enteric fermentation — basically cows (sheep too!) create a lot of methane gas as they digest food.

• The methane gas emitted from manure.

• Nitrous Oxide — another greenhouse gas — released due to use of fertilizers (used for livestock feed as well as other food crops.)

• Deforestation or other land use changes (in some cases) can turn land from carbon sinks (e.g. forests) to carbon sources (e.g. cattle ranches), which is particularly problematic in the Amazon rainforest

Consider switching up a chocolate dessert or a cheesy meal with a delicious alternative some of the time — apple crumble or chicken/veggie burgers anyone?

I have included some sources for climate friendly recipes below. Some are vegan but you don’t have to be vegan to enjoy a plant-based meal here and there.

Some of the innovations being implemented or explored to decarbonize beef:

• Lower Carbon Beef Ranching Practices — (a good step but this beef is still a high carbon food)

• Changing cow diets to reduce methane production — (a good step but this beef is still a high carbon food)

• Lab grown beef

Avoid extremely carbon intensive practices and choose more sustainable versions of given food where possible

a) Air Freighted Perishables

Most foods are not transported by air. However, perishables — like asparagus and berries — often need to be air-freighted, for example, when out of season.

This dramatically increases the Carbon Footprint of these foods (see food lists above.)

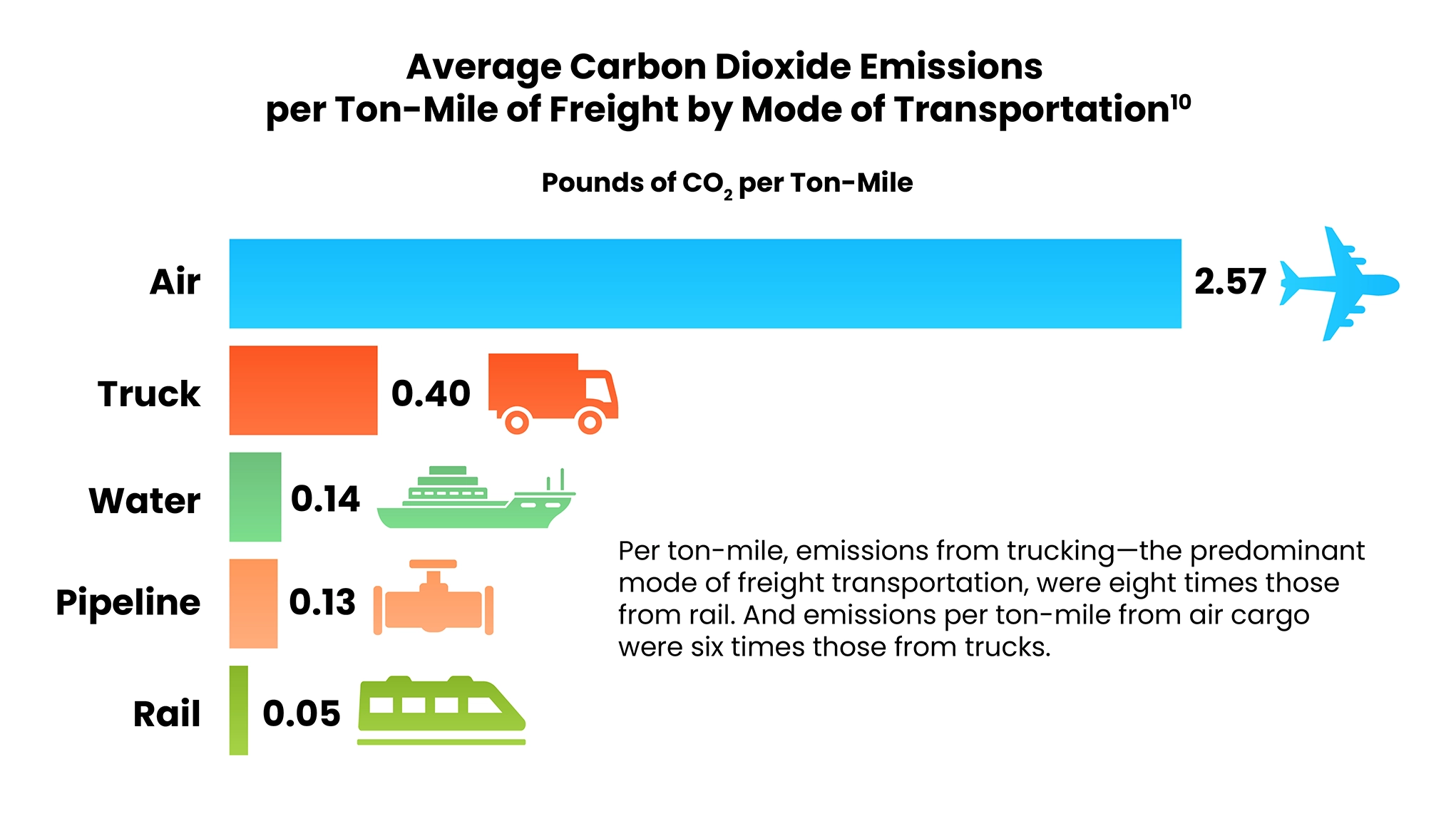

Data from the US also shows the impact of air transport of freight.

According to research by Mike Berners-Lee in the Carbon Footprint of Everything11, cutting out air freighted food from your diet can reduce your footprint by 1-2 tonnes /year (based on average meat and plant-based diets). If you are targeting a 5-tonne lifestyle or even a 10-tonne lifestyle, this is a low-hanging fruit opportunity to significantly reduce your footprint (pun intended!)

Recommendation: Enjoy these foods fresh when in season and find substitutes or frozen/canned options when out of season.

Note: the rise of the tiny plastic containers of year-round perishables is recent. We can shift our habits to undo this trend or at least scale it back a little. Maybe try a substitution every other shopping trip to start. It is an opportunity to save money as well while addressing the climate crisis.

b) Avoiding brands with high intensity because they destroy carbon sinks11.

Seafood

Tiger prawns, shrimp, and lobster — many mangrove forests are destroyed to establish seafood farms in Asia which, like the Amazon rainforest, are really important carbon sinks11. (note: Ocean-trawling is also a carbon intensive practice). Thankfully, there are more sustainable sources of these foods (in Canada!) and also other seafood options.

Choose sustainably sourced options instead.

Palm Oil

Many palm oil farms are grown on converted peat lands which are another really important carbon sink13.

Choose sustainable options (CSPO — certified sustainable palm oil) or alternatives.

Since palm oil is used in a ton of products (food and non-food), it is probably easiest to check your favourite brands and try to replace them with friendlier alternatives and/or become generally more aware of products that contain it — e.g. many pre-packaged baked good, icing, and ice creams — and try to replace them with sustainable alternatives.

Reducing consumption of palm oil is aligned with a healthier diet as well.

Here is a resource to guide you:

Beef

One of the biggest threats to the Amazon rainforest15 — one of the world’s most critical carbon sinks — is clear-cutting for cattle ranching. If you eat beef, buy from domestic/local sources.

Try to avoid unsustainable or unknown sources in packaged products and fast food. Avoid Brazilian beef and try to encourage everyone you know to do the same. Know where your beef comes from.

c) If possible, splurge on sustainable, climate friendly versions of your favourite carbon-intensive indulgences — at least some of the time.

Coffee

If you don’t drink coffee, the climate crisis is a good reason not to start. For some of us addicts, for whom coffee is one of life’s daily pleasures, there are ways to reduce our footprint if you spend a little more money on sustainable options.

Sustainable coffee production has come a long way with many fair trade and sustainable farming brands. These brands tend to support small scale farmers and good farming practices (e.g. less pesticide use).

Some sustainable brands are also low carbon.

Here are a few examples — you can find these across Canada and/or order online:

Chocolate

Try other lower carbon treats e.g. apple pie or fruit parfaits over chocolate cake — some of the time.

Buy low carbon chocolate/support more sustainable brands.

Here are some examples of ones that discuss carbon neutrality:

Many more focus on sustainability but not carbon per se. However, more sustainable brands that focus on preventing deforestation and supporting Regenerative Agriculture will tend to be lower carbon.

Here is one resource to start your research if you are interested…

Cheese

So sad. Cheese is wonderful. But everything in moderation — try to cut back and try different recipes that don’t call for cheese now and again.

Try a vegan cheese sauce (nothing can replace cheese just yet but there are a few vegan cheeses and cheese sauces that are quite delicious and taste very much like a dairy version.)

Among cheeses, lean towards the less carbon-intensive ones.

Again, some carbon intensive foods are typically eaten in small quantities — like parmesan and sour cream, so are not as concerning as ones that are eaten in larger quantities.

And in general, soft, fresh cheeses, and cheeses that do not need to be refrigerated for long periods of time are better than hard, dry cheese and long-refrigerated cheeses (though the biggest part of the footprint for cheese is animal production.)

Also, many farmers are on board with addressing climate change and are working towards solutions that reduce the Carbon Footprint of their products. For example, the Dairy Farmers of Canada have a Net Zero 2050 plan that they are working towards. You can read more about it here.

Higher carbon foods today will likely become medium or low carbon foods in future.

Avoid wasting food wherever possible — especially carbon intensive food

Remember when you waste food you are wasting all of the CO2 (and water) that were used to produce, process, package, transport and house the food at the grocer as well as at your house.

Composting/green bins are good but it is far better to avoid waste in the first place.

Food waste occurs for many reasons:

• Buying more than you need.

• Poor meal planning so food isn’t used up before it expires.

• Poor meal planning so more food is prepared than can be eaten and leftovers are tossed.

• Improper storage of food.

• Food is forgotten in the pantry and expires.

• Best before and use by dates are misunderstood and consumable food is pre-emptively tossed.

Here are some resources to help you waste less food:

At the systemic level, there is a lot of work being done in Canada to reduce food waste as well.

Some examples:

Keep things in perspective — adopting a climate friendly diet will have a positive impact, but not on the scale of a single piece of chocolate. Enjoy your food.

Make the focus about conscious, healthy eating and don’t feel guilty about small or occasional indulgences or the time it takes to build new habits.

You will have a bigger impact overall by generally shifting your diet and changing your shopping/cooking behaviours while also focusing on big rock changes (home heating/driving), general consumption, and using your voice and vote to drive change.

Packaging and plastic pollution

The other major piece of the food waste problem is plastic packaging.

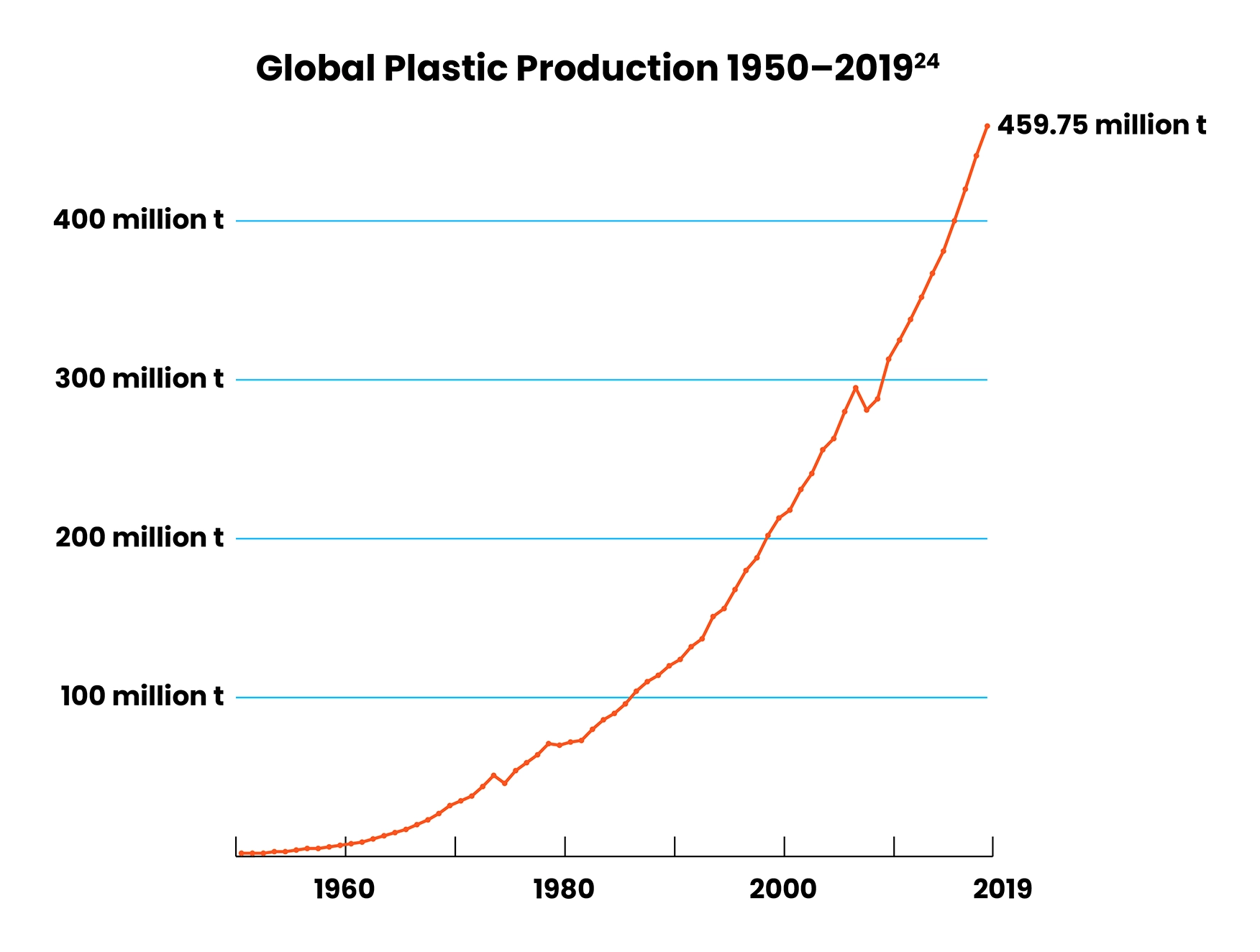

In 2019, plastics generated 1.8 billion tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions (90% coming from their production and conversion from fossil fuels) and this is projected to double by 2060 if we don’t change.

Leakage of package waste into the environment has been documented in all major oceans, beaches, lakes and terrestrial environments. It was estimated to be 22 million tonnes in 201918 and is also expected to double by 2060 without intervention.

We all know about the incredible amount of harm microplastic waste has had on marine and terrestrial wildlife. Exposure to microplastics is also ubiquitous, posing threats to wildlife and, as recent evidence indicates, human health as well19.

Canadians throw away over 3 million tonnes of plastic waste every year, of which only 9% is recycled20.

Plastics are used all along the value chain in our food systems and, of course, outside of our food systems.

Back in 2018, it was estimated that packaging of goods accounted for about 40% of all plastics produced and 41% of that is for food and beverage packaging21.

A more recent report in Canada showed that more than 70% of products in produce and baby food aisles are packaged in plastic which exposes us to microplastics and creates plastic pollution22.

The latter are mostly single use plastics that many governments are beginning to regulate, find alternatives to and/or develop a circular economy around (e.g. more extensive recycling). Canada is no exception20.

How can we take personal action to avoid plastic pollution and microplastic exposure as it relates to our food?

• Don’t buy plastic water/beverage bottles. Choose glass or use re-usable bottles wherever possible.

• Buy unpackaged produce wherever possible and bring your own re-usable bags rather than using the plastic ones at the store or don’t use a produce bag at all.

• Make sure you put your re-usable bags in your car or by the door so you don’t forget them!

• Bring a set of cutlery (bamboo travel cutlery sets are great!) if you eat at places that use plastic cutlery and ask takeout vendors to skip the cutlery and condiments if you are eating at home.

• Bring your own container to restaurants if you often take home leftovers.

• Buy eggs in a paper carton.

• Get meat and cheese from the deli counter and ask for paper wrapping if available.

• Buy compostable trash bags.

• Buy bread from bakeries that package in paper.

• Use re-usable zip bags, cloth food covers, and/or bees wax to wrap food/dishes instead of ziplocks or clingwrap.

• Buy foods and beverages in glass containers or cartons where possible rather than plastic or cans—the latter contain BPA which can leach into food.

• Buy butter in cardboard and foil rather than plastic containers.

• Buy prepared foods in cartons rather than plastic.

• Buy goods at bulk stores or zero waste stores and store them in glass containers.

• Soak rice for 30 min in filtered water before cooking to wash off microplastics.

• Reduce fish and shellfish intake, including canned tuna.

• Wash produce with a vinegar bath to remove microplastics.

• Filter water you use for cooking and drinking.

• Use loose leaf tea in a steel or silk infuser or source tea bags that are not made of or coated with plastic.

• Replace any plastic cutting boards with bamboo/wood ones.

• Use this site to look up BPA free canned goods — note that the amounts of BPA in canned goods is extremely low relative to levels that are currently considered safe. It’s the accumulated exposure to microplastics from many sources that recent research is finding may be problematic.

• Try to find plastic free stores near you — for example, here is a resource for Ontario.

• Cook and bake your own food rather than buying pre-packaged, prepared food if possible.

For perspective, although it feels as though we can’t live without plastic, the plastic problem is recent.

44% — the proportion of plastic generated since 2000 as compared to all plastic since 195023.

“In the early 2000s, the amount of plastic waste we generated rose more in a single decade than it had in the previous 40 years”18.

We can take a step back and move in a different direction or at least shift our habits to allow time for more circular and non-damaging solutions.

Costs — Impact of a climate friendly diet on your wallet

Shifting your diet to mitigate the climate crisis will also save you money.

More broadly as well, research has shown that sustainable, low greenhouse gas diets have been shown to have lower costs than unsustainable, high greenhouse gas diets27.

A low carbon diet is a great starting point for a healthy, sustainable diet. There is a lot of overlap between a low carbon diet and a diet focused on healthy eating habits and sustainability more generally28.

World Health Organization and UN Food and Agriculture Organization list the following as principles of a healthy sustainable diet.29

• Are based on a variety of unprocessed or minimally processed foods balanced across food groups, while restricting highly processed food and drink products.

• Include whole grains, legumes, nuts and an abundance and variety of fruits and vegetables.

• Can include moderate amounts of eggs, dairy, poultry, and fish and small amounts of red meat.

• Includes safe and clean drinking water.

• Are adequate — reaching but not exceeding — in energy and nutrients for growth and development to meet the needs for an active and healthy life across the lifecycle.

• Are consistent with WHO guidelines to reduce the risk of diet-related non-communicable diseases and ensure health and wellbeing for the general population.

• Contain minimum levels (or none) of pathogens, toxins, and other agents that can cause food borne disease.

• Maintain GHG emissions, water and land use, nitrogen and phosphorus application, and chemical pollution within set targets.

• Preserve Biodiversity, including that of crops, livestock, forest-derived foods and aquatic genetic resources and avoid overfishing and overhunting

• Minimize use of antibiotics and hormones in food production.

• Minimize the use of plastics and derivatives in food packaging.

• Reduce food loss and waste.

• Are built on and respect local culture culinary practices, knowledge, and consumption patterns and values on the way food is sourced, produced and consumed

• Are accessible and desirable.

• Avoid adverse gender-related impacts, especially with regard to time allocation (eg. for buying and preparing food, water and fuel acquisition.)

Note that if you are aiming to shift to a more sustainable, low carbon diet, you might want to consider additional adjustments based on water use (e.g. limit consumption of almonds/almond milk), human rights concerns (e.g. limit consumption of avocados from Mexico/Central America), etc. and a healthy diet may consider additional considerations such as heavy metal content (e.g. lead in dark chocolate.)

“Regenerative agriculture takes a systems-based, holistic look at the land being stewarded and applies various principles with the goal of making the land more productive and biodiverse over time. In most situations, improving soil health and function is the key to improving productivity and Biodiversity. One of the key components of healthy soil is organic matter, which is anything that is alive or was once living, such as a plant root, an earthworm, or a microbe.” — Kiss the Ground for Regeneration

Regenerative Agriculture has many sustainability benefits and can also reduce costs of production for farmers.

One key sustainability benefit is that regenerative practices mitigate climate change by reducing emissions related to food production inputs and processes and also by sequestering more carbon in the soil, increasing the capacity of farmland to act as a carbon sink. Healthy soils also generate healthy foods.30

You can support regenerative farming directly and/or learn more using the following resources:

Canada is investing in Agricultural climate solutions that use many of the principles of Regenerative Agriculture31. Supporting government action and funding dedicated to helping more farmers shift practices to adapt to and mitigate climate change is critical to meeting our Net Zero targets.

And many organizations are also promoting climate change mitigation in Canada’s food system such as The Canadian Alliance for Net Zero Agri-food and The Arrell Food Institute.

There is a lot of innovation and implementation of climate change mitigation initiatives occurring in Canada that inspire confidence that we will reach Net Zero.

But we are not on track yet. The more you can do to support emissions reductions in the food system, allowing time for more systemic changes to occur — the closer we will get to our 2030 and 2050 targets.

It’s easy, fun, provides fresh delicious food and can be big or small, planted in pots/containers, raised beds, or a ground level plot and can have as little or as much variety as space, time, and preferences dictate.

Summary of potential actions

• Reduce/eliminate high carbon foods (especially beef) — even if temporarily

• Increase proportion of low carbon foods in your diet

• Buy sustainable versions of given foods

• Reduce food waste

• Reduce purchase and use of plastic packaging

• Use sustainable habits when you eat out

• Support sustainable agriculture

• Support government policies around sustainable farming

• Support food waste programs

• Support systemic change in the food and food service industry

• Advocate for sustainable farming/fishing/packaging/food options

• Grow a garden

• Share your progress with others / learn from others

Ready to get started? Build a plan that works for you here.

References

1. Lang, T., Li, G., & Mattie, S. (2022, March 28). Data for Canadian Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions attributable to household consumption and use of select goods and services along with the associated emissions intensity figures and breakdowns by final demand categories. Government of Canada, Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-627-m/11-627-m2022003-eng.htm

2. Charles, A. (2021, June 16). New research shows Food System is responsible for a third of global anthropogenic emissions. UNIDO. https://www.unido.org/stories/new-research-shows-food-system-responsible-third-global-anthropogenic-emissions#:~:text=VIENNA%2C%2011%20June%202021%20%2D%20The,NASA%20and%20several%20policy%2Dfocused

3. Ritchie, H., Rosado, P., & Roser, M. (2022, December 2). Environmental impacts of food production. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/environmental-impacts-of-food?insight=food-emissions-climate-targets#key-insights-on-the-environmental-impacts-of-food

4. Environment and Climate Change Canada. (2022). 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan — Canada’s Next Steps for Clean Air and a Strong Economy. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2022/eccc/En4-460-2022-eng.pdf

5. Maslin, M. (2022, September 7). Climatarian, flexitarian, Vegetarian, vegan: Which diet is best for the planet? (and what do they mean?). ideas.ted.com. https://ideas.ted.com/which-diet-is-better-for-climate-change-vegan-vegetarian-climatarian-flexitarian/

6. Ritchie, H., & Roser, M. (2023, September 27). Food production is responsible for one-quarter of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/food-ghg-emissions

7. Ritchie, H., Rosado, P., & Roser, M. (2022a, December 2). Environmental impacts of food production. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/environmental-impacts-of-food?insight=differences-carbon-footprint-foods#key-insights-on-the-environmental-impacts-of-food

8. Ritchie, H., & Roser, M. (2023b, November 10). You want to reduce the Carbon Footprint of your food? focus on what you eat, not whether your food is local. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/food-choice-vs-eating-local

9. Greenhouse gas emissions and agriculture. Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. (2023, July 10). https://agriculture.canada.ca/en/environment/greenhouse-gases

10. Emissions of carbon dioxide in the Transportation Sector. Congressional Budget Office. (2022, December). https://www.cbo.gov/publication/58861#:~:text=In%202019%2C%20CO2%20emissions,all%20lower%20per%20passenger%2Dmile

11. Berners-Lee, M. (2022). The Carbon Footprint of everything. Greystone Books. Buy here.

12. Pyjar, L. (2021, May 13). (shell)Fisheries – a source of surprisingly high carbon emissions. Eat Blue. https://www.eat.blue/animal-welfare/shellfisheries-a-source-of-surprisingly-high-carbon-emissions/;

Kauffman, J. B., Arifanti, V. B., Trejo, H. H., del Carmen Jesús García, M., Norfolk, J., Cifuentes, M., Hadriyanto, D., & Murdiyarso, D. (2020, April 18). The jumbo Carbon Footprint of a shrimp: carbon losses from mangrove deforestation. CIFOR. https://www.cifor.org/knowledge/publication/6431/

13. EFECA. (2022, January). Carbon Emissions and palm oil. https://www.efeca.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Palm-Oil-and-Carbon-Emissions_final.pdf

14. What is Certified Sustainable Palm Oil CSPO?. CSPO Watch. (2023). https://www.cspo-watch.com/defining_sustainable_palm_oil_cspo.html

15. Cederberg, C., Martin Persson, U., Neovius, K., Molander, S., & Clift, R. (2011, January 31). Including Carbon Emissions from Deforestation in the Carbon Footprint of Brazilian Beef. ACD Publications. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/es103240z#:~:text=The%20carbon%20footprint%20of%20beef,pasture%20on%20non%2Ddeforested%20land;

Kimbrough, L. (2022, October 18). Beef is still coming from protected areas in the Amazon, study shows. Mongabay Environmental News. https://news.mongabay.com/2022/10/beef-is-still-coming-from-protected-areas-in-the-amazon-study-shows/;

Ledur, J., & McCoy, T. (2022, April 29). How americans’ Love of beef is helping destroy the amazon rainforest. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/interactive/2022/amazon-beef-deforestation-brazil/

16. UNEP. (2021, March 4). UNEP Food Waste Index Report 2021. https://www.unep.org/resources/report/unep-food-waste-index-report-2021

17. Food waste in the home. Love Food Hate Waste Canada. (2022, May 6). https://lovefoodhatewaste.ca/about/food-waste

18. UNEP. (n.d.). Visual feature: Beat plastic pollution. https://www.unep.org/interactives/beat-plastic-pollution/

19. Li, Y., Tao, L., Wang, Q., Wang, F., Li, G., & Song, M. (2023). Potential Health Impact of microplastics: A Review of Environmental Distribution, Human Exposure, and Toxic Effects. ACS Publications. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/envhealth.3c00052;

Lee, Y., Cho, J., Sohn, J., & Kim, C. (2023, May). Health effects of microplastic exposures: Current issues and perspectives in South Korea. Yonsei medical journal. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10151227/;

Campanale, C., Massarelli, C., Savino, I., Locaputo, V., & Uricchio, V. F. (2020, February 13). A detailed review study on potential effects of microplastics and additives of concern on human health. International journal of environmental research and public health. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7068600/

20. Government of Canada. (2023, April 14). Plastic waste and pollution reduction. https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/managing-reducing-waste/reduce-plastic-waste.html

21. Yates, J., Deeney, M., White, H., Joy, E., Kalamatianou, S., & Kadiyala, S. (2019, July 19). PROTOCOL: Plastics in the food system: Human health, economic and environmental impacts. A scoping review. Wiley Online Library. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/cl2.1033

22. Environmental Defence Canada. (2023a, May 2). Left Holding The Bag — A Survey of Plastic Packaging In Canada’s Grocery Stores. https://environmentaldefence.ca/report/left-holding-the-bag-plastic-packaging-in-grocery-stores/

23. Parker, L. (2021, May 4). Fast facts about plastic pollution. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/plastics-facts-infographics-ocean-pollution

24. Ritchie, H., Samborska, V., & Roser, M. (2023). Plastic pollution. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/plastic-pollution

25. Milbrath, S. (2021, December 1). 8 food waste facts that every Canadian should know. Second Harvest Blog. https://blog.secondharvest.ca/2021/12/01/food-waste-facts-every-canadian-should-know/

26. Government of Canada, Statistics Canada. (2022, March 16). Monthly average retail prices for food and other selected products. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1810000201&cubeTimeFrame.startMonth=02&cubeTimeFrame.startYear=2018&cubeTimeFrame.endMonth=02&cubeTimeFrame.endYear=2022&referencePeriods=20180201%2C20220201

27. Springmann, M., Clark, M. A., Rayner, M., Scarborough, P., & Webb, P. (2021, November). The global and regional costs of healthy and sustainable dietary patterns: A modelling study. The Lancet. Planetary health. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8581186/; Conrad, Z., Drewnowski, A., Belury, M. A., & David C. Love, D. C. (2023, April 17). Greenhouse gas emissions, cost, and diet quality of specific diet patterns in the United States. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0002916523468475

28. Lucas, E., Guo, M., & Guillén-Gosálbez, G. (2023, May 15). Low-carbon diets can reduce global ecological and health costs. Nature News. https://www.nature.com/articles/s43016-023-00749-2; Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. (2023, March 7). Sustainability. The Nutrition Source. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/sustainability/; Towards more sustainable diets. Eufic. (2018, April 19). https://www.eufic.org/en/food-production/article/towards-more-sustainable-diets

29. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, World Health Organization. (2019). Sustainable Healthy Diets: Guiding Principles. WHO. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/112642/9789241564748_eng.pdf;jsessionid=3DFA76135096412FF7041954E144562E?sequence=1

30. Why Regenerative Agriculture?. Regeneration International. (2024, January 2). https://regenerationinternational.org/why-regenerative-agriculture/

31. Government of Canada. (2023, July 24). Agricultural Climate Solutions. Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. https://agriculture.canada.ca/en/environment/climate-change/climate-solutions